Time to dry off: understanding how moisture content affects cross-laminated timber

Over the past two decades, cross-laminated timber – CLT – has slowly but surely increased in popularity as a construction material. It’s easy to see why, as CLT can be deployed in a range of applications, including complex timber structures for residential, educational and commercial builds. Moreover, it offers exciting opportunities for low, or even negative, carbon construction.

Executed well, timber-based buildings can remain in service indefinitely – indeed, lightweight timber-frame buildings have been used for nearly 100 years. What’s more, a large proportion of the UK housing stock features pitched timber roofs, many of which are centuries old. However, given the ‘newness’ of this CLT, there’s been a learning curve in terms of understanding its strengths and weaknesses. Crucially, as with all varieties of timber, moisture can have a significant impact on durability and longevity.

Drying times & decay

One of the biggest risks facing timber buildings is fungal decay, which can occur if the moisture content within the building product exceeds 20% for an extended period of time. In a well-designed timber- frame building or pitched roof, moisture content in service will be between 10% and 14% – well below the fungal decay threshold.

CLT follows the same durability principles as lightweight timber structures, but owing to its thickness and mass of timber used, it can present additional considerations when exposed to moisture. For example, timber studs, joists and rafters have a relatively large surface-area-to-volume ratio and so typically dry rapidly when conditions allow. CLT however, has a much smaller surface-area-to-volume ratio, meaning drying rates can be substantially slower and ultimately affect the endurance.

Insulation & limited drying

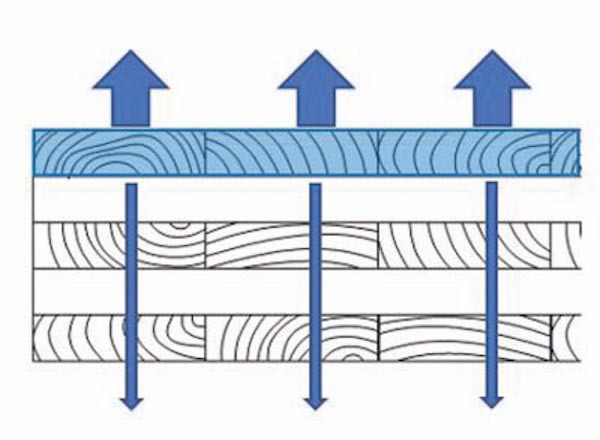

Another prominent factor that can affect CLT drying time is insulation. CLT external walls and roofs should always be designed as ‘warm’ construction. This means that all thermal insulation is placed on the wall’s outside face or roof panel. Putting the CLT panels within the building’s thermal envelope should facilitate a warm and dry environment, thus allowing timber to survive and last.

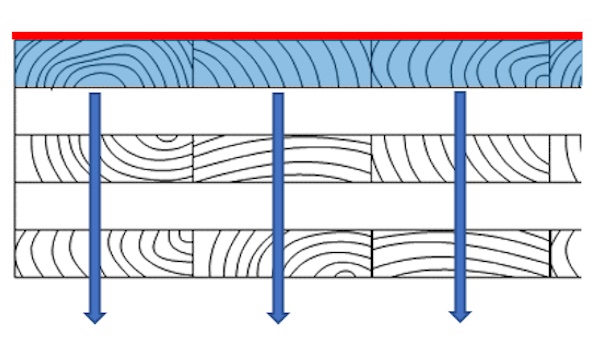

In the UK, the most common insulation material placed on the outside of CLT has been rigid foil-faced insulation boards – e.g., PIR/PUR/phenolic – which are installed to walls, flat roofs and pitched roofs. While these insulation materials have excellent thermal resistance and provide the necessary U-values for a given thickness, the foil facings limit the ability for the CLT panels behind to dry effectively.

Historically, it was assumed that any wetting to the CLT panels – either through trapped construction moisture or cladding leaks/water ingress in service – would be able to dry through the panel to the building’s interior; however, this was just a widely held assumption.

Moisture dynamics: new data & research

To improve decision making and construction, BM TRADA and Stora Enso conducted research to better understand CLT’s moisture dynamics. The two-part project looked at both wetting risk during construction and drying rates, serving as information that can be used to determine moisture distribution behaviour.

A fundamental part of the research was observing drying rates of five-layer, 100mm-thick CLT panels. Various configurations were tested, including covering the wet outer face of panels with foil to replicate those covered with rigid foil-faced insulation boards and/or vapour control layers. This test set-up was intended to imitate typical UK construction build-ups for warm walls as well as flat and pitched roofs.

In testing the covered panels, water in the wet outside face lamination was seen to be slowly passing through the panel’s thickness to the dry uncovered side, confirming the previously held assertion that panels could dry to the inside. That said, with a starting moisture content of 35% in the wet outer lamination, it took almost 16 months for the moisture content to fall to 20%. For higher moisture contents and/or thicker panels, this means it could take years for the timber to dry. On the flip side, uncovered panels that were able to dry directly from the wet face took approximately six weeks for a similar moisture content reduction.

Breathability is the key

Achieving long-term durability of timber structures depends on a primary consideration – breathability. To provide this, there must be a good combination of drainage and ventilation. If timber gets wet, it’s not usually problematic, provided that water can drain away swiftly, and the timber is then allowed to dry. However, issues can start to occur if timber drying times are slowed down or restricted by the use of high resistance insulation products and/or vapour control layers on the panels’ inner or outer faces. These can cause drying to decelerate to an extent that the development of fungal decay may become a risk, especially if panels are subjected to adverse conditions during construction or in service.

Looking over to European construction methods, CLT building systems are often paired with mineral wool or wood-fibre insulation products. Typically, these are more beneficial to timber construction as such breathable insulation materials allow for faster drying of the CLT panels if they’re exposed to wetting.

In summary, the use of breathable insulation products and systems, paired with good overall design and an effective moisture management plan, will have a considerable positive impact on the long-term durability and robustness of CLT structures.

Planning ahead

CLT will certainly have a role to play in the move to creating greener, low carbon buildings. However, to ensure that CLT buildings are successful, it’s crucial to know how to protect the material against moisture ingress. When moisture content does pose an issue, it’s important to take action straight away. These considerations should be made at the start of any timber construction project, and it’s notably important to plan in time for timber to sufficiently dry in order to prevent the onset of fungal and structural decay.

For more information on BM TRADA and its range of timber services, visit www.bmtrada.com/timber-services.

- Log in or register to post comments